Summer Explorations in Dance & Theatre – MFA explorations

[fblike]

This feels like a child’s “what I did this summer” school essay, which is and isn’t true. Knowing I was starting at Goddard in July, I went out this summer on a mission to see as much theatre and dance as I could. So, I was in school mode and trying to be childlike and excited about opportunities I might not have let myself take advantage of because of silly “adult” excuses – too busy, too expensive, too tired… But the good little schoolgirl, Jessica, took my hand and we experienced many fun and interesting moments in the performing arts this summer – all with my older, critical eye.

Luckily, my work was in the Berkshires so I had many opportunities to see a variety of pieces. I was curious on how I chose them, or they chose me sometimes when it came to opportunity, time and family/work obligations. In the end, I was lucky enough to enjoy two plays at the Williamstown Theatre Festival, a dance theatre performance and master class at Jacob’s Pillow. All four events contributed to my focus at Goddard in different ways.

“A Streetcar Named Desire” had just opened in the Nikos Theatre at Williamstown Theatre Festival. The murmurings around town were about four things: the new artistic director of the festival, Jenny Gersten, the play’s director, David Cromer, the star, Sam Rockwell and the re-imagining of the Nikos Theatre playing space.

“A Streetcar Named Desire” had just opened in the Nikos Theatre at Williamstown Theatre Festival. The murmurings around town were about four things: the new artistic director of the festival, Jenny Gersten, the play’s director, David Cromer, the star, Sam Rockwell and the re-imagining of the Nikos Theatre playing space.

I love Streetcar and feel like I know it backwards and forwards, so I was not all that interested in seeing it until I heard that 2010 MacArthur Fellow, David Cromer, was directing it. Cromer made a big splash with his direction of a musical version of The Adding Machine and his deconstructed version of Our Town, which he directed on and off-stage by also playing the role of the Stage Manager. His work is centered on examining American life through American playwrighting. He does not tend to work in classic or international text. Cromer also extends art into reality and reality into art in a very Brechtian way at times. For instance, in the first two acts of Our Town the house and stage lights are on as if the audience is watching a rehearsal. There is no boundary between audience and play. This all pulled me in to see how he would envision Streetcar.

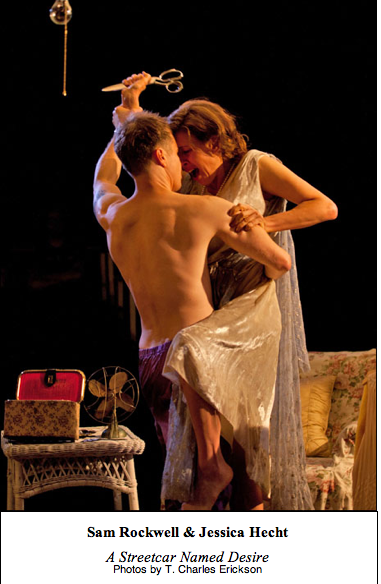

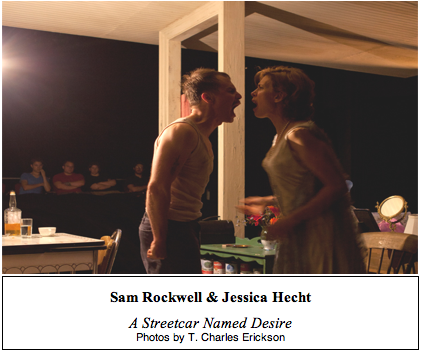

I found the world he created was both naturalistic and fantasy, from the street noises blending into music and back again to the minimal, actor manipulated lighting (bare bulbs in the apartments). He developed a tight knit ensemble that built up to a wonderful vocal spin to Blanche’s final breakdown and exit. Their voices muttered everything that was said to her creating a distant, flat echo. The audience was practically on top of the action, with seating on stage, putting the set in a galley situation with the audience on both sides of the skeleton apartment looking in.

Cromer filled the evening with strong relationship development, interesting physical choices and a break-neck pacing that slowed down in the sweltering heat only to explode in such tight spaces. There was no “star” in this production, as there are normally roles that take the spotlight, but here they were all part of the world equally. I think this is due to the fact that Cromer discovered and articulated each thread that holds the characters together, so it was impossible to imagine it with less or more people. Each person was not only relevant but vital to the action, atmosphere and momentum of the piece. The only problem I had with the show was the final rape and stage combat. The violence up that point was visceral and spot on, but the struggle to the rape scene with Stanley and Blanche was confusing/anti-climatic. Throughout the show, Blanche’s dead husband would appear as if haunting her.

First, during her monologue to Mitch first describing how she found her new husband dead from self-inflicted gunshot wound. Then, after her date with Mitch, going back into her bedroom to see her dead husband and his lover on her bed (a reenactment of what happen the night he committed suicide). And finally, he sits on her bedrail during her call to her fantasy beau in Texas, right before Stanley comes home, as her voice is altered through sound effects to reverberate and sound distant.

All this builds up to the struggle and rape of Blanche by Stanley. But in this production, after the struggle there is a held moment with Blanche defending herself with scissors and Stanley grabbing her and the arm holding the shears. The hold this moment in a quiet struggle for quite sometime, longer than felt right, longer than felt possible… and then he easily throws her on the bed, face down, and throws the scissors on the floor. Black out. So, the question becomes, does he rape her? It’s an interesting question and can be supported a bit with the text afterwards between Stanley’s wife, Stella, and her upstairs neighbor, Eunice:

STELLA: I don’t know if I did the right thing.

EUNICE: What else could you do?

STELLA: I couldn’t believe her story and go on living with Stanley.

EUNICE: Don’t ever believe it. Life has got to go on. No matter what happens, you’ve got to keep on going. (Williams, 11)

Yes, Blanche was prone to elaborate tales and sometimes, pure fabrications, but this seems outside of anything Williams’ was building up to. And in these modern times, I’m sure it is hard to imagine a man coming home from the hospital where his wife has just had their first son only to get drunk and rape his sister-in-law. It is atrocious but when women are looked at as less than men, as either Madonna or whore, and given Stanley’s drunken rages and dominant sexual energy seen from moment one of the play, the rape isn’t out of the realm of possibilities. I think that Cromer was leading up to a very interesting interpretation of the play but the switch over to it being merely in Blanche’s head (if that was truly the intention) fell short. But maybe that wasn’t what he was going for… as I read many reviews of this production, and the original one staged in 2010 at Chicago’s Writers’ Theatre, no one else has mentioned such an interpretation of this moment. Curious.

Cromer’s casting for this and the Chicago production were against type, for both Stanley and Blanche. He ignored previous popular casting of Blanche as frail and Stanley as a muscular beast. Instead, he flipped the energy and directed Blanche as a strong willed, loud, neurotic woman, played by Jessica Hecht, and Stanley a small, wiry, angling man with a severe temper. This really upped the stakes for Stella, truly being caught between a rock and a hard place.

Cromer’s casting for this and the Chicago production were against type, for both Stanley and Blanche. He ignored previous popular casting of Blanche as frail and Stanley as a muscular beast. Instead, he flipped the energy and directed Blanche as a strong willed, loud, neurotic woman, played by Jessica Hecht, and Stanley a small, wiry, angling man with a severe temper. This really upped the stakes for Stella, truly being caught between a rock and a hard place.

The unique casting of Sam Rockwell was also an amazing lure for me. I have been studying Rockwell’s work onscreen for years from his smaller independent films to his big budget blockbusters. No matter how tight or flimsy the script, whether it be dramatic or comedic, Rockwell attacks each role with such an intensity that it seems hard to sustain. I was curious to see how he would transfer this approach on stage, knowing it is different than the stop and start, non-linear world of film. Like few American actors of his level, he balances theatre and film extremely well, holding on to his theatre roots as a long-term member of ensemble theatre company, LAByrinth, started close to the same time he started working in TV and film.

His performance was the spine of the play, which says a lot for this tightly directed ensemble piece. Rockwell used the set as his jungle gym – jumping on the bed, swinging from the door jamb and kicking up the stairwell like an ape swinging from a tree destroying all in his path to claim his place in the pack. But with perfect balance, Rockwell truly listened, he sat actively sat back and heard each moment new. It gave such wonderful space to hear and understand the text in a new way. It was also a terrific tension after seeing what kind of violence and untamed outbursts his character, Stanley Kowalski, is capable of. I must note that this was also supported strongly by how the ensemble reacted to his every breath or change in gaze. They set him up as unpredictable and the silences were not stagnant, they were tense calms before the storm.

The smaller venue, Nikos, is traditionally proscenium seating with 96. It’s intimate but still removed in the way that proscenium stages create and “us and them” boundary. But with David Cromer’s vision and Collette Pollard’s set design, they completely altered how this venue will be seen from here on out. The set was the Kowalski’s one-bedroom apartment seen from the side with narrow dimensions and low ceiling. There was even overhead room enough to build a staircase and covered room above where the neighbors resided. The naturalistic set was just that natural not literal. There were no walls except for the bathroom. The audience, seated in the round with many rows of seating on stage, was able to see through the lives of Tennessee Williams’ play. It felt as if the stage had been extended and rows had been taken out of the theatre to enable the apartment to sit on our laps, and yet that was not so. This set design and directorial concept actually added many things to the Nikos rather than take away. It added more seating, more intimacy and more immediate connections to the action and energy of the ensemble.

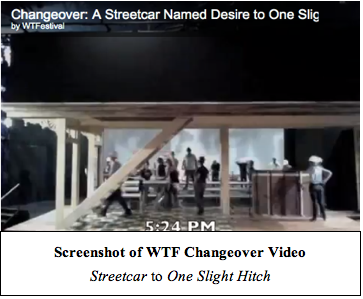

I felt a lot of what this re-imagining gave but I was able to see the nuts and bolts of how it was done through WTF’s new Internet marketing and outreach. Thankfully they have started utilizing their blog, “Within the Festival”, had a YouTube video of the 25-hour change over from A Streetcar Named Desire to their next production of One Slight Hitch. This is a wonderful concept and honoring of the behind the scenes ensemble of the technical crew. A camera was set up in the back of the house and recorded the entire process (a time counter rolls on the bottom of the screen). Every ten seconds or so the hour would appear across the screen to help with perspective. There was also a brief explanation by the Assistant Production Manger of Operations, Kathleen Reinbold, of how many crew members,breaks, shifts etc. were a part of this process. Before my eyes, I can see the inner workings of not only two production’s set, lighting and prop designs but also the smooth running machine of a 57-year old festival producing eight shows in two months, not to mention their free theatre offerings and staged readings.1

This is one of many reasons that I was excited about the new artistic director, Jenny Gerstein. Her history with WTF is a classic example of the way most performing arts companies run, good and bad. She was an associate producer for nine years working on “more than 90 productions of new and classic plays to the stage, with five of them transferring to Broadway.” When her mentor, Michael Ritchie, left the position of Artistic Director, she put her hat in the ring but Roger Rees got the job for the next three years, then Nicholas Martin for three more. “She describes the rejection as painful, and she decided to leave Williamstown altogether,” moving on to NYC as Naked Angels’ Artistic Director and then as associate producer for three years at the Public Theatre. Hearing the position was opening yet again, Gerstein applied, with reservations, “I wasn’t sure if I wanted to come back here. In fact my instinct was to say no at first. I thought, ‘Does this feel regressive?’” It all worked out and in hindsight she says she was happy that they did not give her the job in 2004. She felt it forced her out into the world to gain different experiences with different companies. This is a clear and balanced vision for why venturing out of one’s home (artistic or otherwise) is important to gain exposure, perspective and a voice of one’s own before venturing back home – if the road leads that way. 2

New in the seat, she says she was, “hired as the head of the Festival. That encompasses the duties of artistic director, as we know them traditionally. But there is also a CEO aspect of my job.” She now has artistic connections that she is already bringing in to the festival, including director/creator John Doyle, who’s re-imagining of Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd and Company made big waves on Broadway. Gerstein hired him to open a new musical Ten Cents a Dance based on the works of Rodgers and Hammerstein. Other changes to the season can be seen as “conducting a small but potentially risky experiment. She reduced the number of main-stage shows to three from four (but extended several of their runs, in the hope that word of mouth can build) and added a fifth production to the Nikos.” This is just the beginning and there were hiccups, like one Mainstage musical having to be dropped out quickly and replaced. But I am excited to watch her develop the festival with her blend of business savy and artistic searching. She told the New York Times, ““I have maybe a dozen grand ideas, and they run the gamut — anything from ‘What if we became like a Sundance-type of place?’ to ‘What if we did entirely avant-garde work?’ It’s probably not going to be any of those specific things. But I love the idea that it’s something in between. As much as I want to embrace the Williamstown I know and love, I also think there’s enormous possibility for what the festival could become.” 3

The season also reflects her first steps at bridging the two worlds of Williamstown with an audience base’s expectations established from previous seasons and the potential of WTF. To balance this, s invited back former artistic director, Nicholas Martin, to direct She Stoops to Conquer. She also set up informal question and answer sessions throughout Williamstown to engage the year-round community, for example, having A Streetcar Named Desire’s director, David Cromer, speak to the Rotary Club about his new take on the classic Tennessee Williams play. In an interview with Charles Giuliano for Berkshire Fine Arts’ website, Gerstein delved deeper into her hopes for WTF, “It’s going to be a great mix of plays that people really want to see. And picking plays that people didn’t know they wanted to see but are a revelation. Like Forum last summer. There’s a lot to the story yet to be told about the education programs at Williamstown. What that lends to the overall atmosphere and energy. It’s a Theatre Festival and I want to keep talking about those aspects and what is being home grown in the fellowship projects. Like After the Revolution last year. [Amy Herzog’s play that moved to Playwrights Horizon the next season.] People don’t really know about that. It is some of the most important new play development happening in American today and people don’t really know about it.” 4

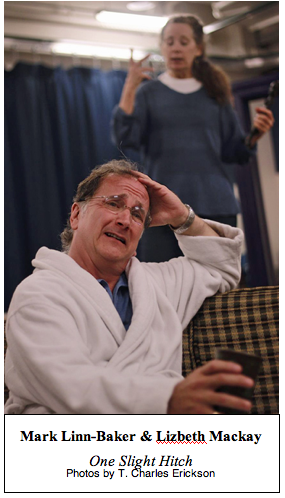

I was also able to the next production mounted on the Nikos Stage, comedian Lewis Black’s modern farce, One Slight Hitch. It was sherbert after a heavy meal, going from one show to the other. I enjoyed the light-hearted nature of the piece. It’s a romantic farce Black wrote 30 years a go while in college with the play’s director, Joe Grifasi, and lead actor, Mark Linn-Baker. The play takes place in the 80’s at a bride-to-be’s family house on the day of her wedding. Unexpectedly, her former boyfriend appears out of nowhere and raises doubts in the bride and as they say… hilarious antics ensue.

The set was a definite literal flashback to suburan 80’s life, pastel florals and doors a’plenty to throw someone into and run in and out of – a necessity for farce. The acting was both wonderful and okay, which is hard for an ensemble show such as this. A few raised the bar with sharp timing underscored with natural honesty: Mark Linn-Baker (Doc Coleman), Justin Long (Ryan) and newcomer Clea Alsip (Melanie Coleman). They showed that even in a broad farce, truth is possible and I would argue that the truth makes it funnier. But that was often countered with actors that were either directed to be broad or were pushing their energy to a place out of their reach in order to keep the pace. The truth kept slipping through the ensemble’s hands when the above three actors weren’t present to ground it in solid comedic acting.

Above all, Mark Linn-Baker was a joy to see on stage. He is clearly getting richer with age and making more and more use out of his solid clown and mime training. The crisp focus that could turn on a dime, necessary when things really get rolling in a farce, helped guide the audience by the hand with the momentum of running down hill. It was all too apparent how much was riding on his performance when he stole the show on stage alone during a “conversation” with the in-laws. At this point in the play, the wedding preparations are in high gear; the ex-boyfriend has arrived and is hidden in the bathroom; and ‘ding dong’ the future in-laws are at the door. In a drunken frenzy (yes, the father of the bride – trying to keep everything under wraps – has had a few stiff ones already) Doc Coleman must turn the in-laws around and send them to a hotel. In this production, there are no actors playing the in-laws. So the audience sees only Doc juggling lies, polite courtesies and suitcases into an open doorway. The scene lasted a glorious 10 minutes and stole the show.

Above all, Mark Linn-Baker was a joy to see on stage. He is clearly getting richer with age and making more and more use out of his solid clown and mime training. The crisp focus that could turn on a dime, necessary when things really get rolling in a farce, helped guide the audience by the hand with the momentum of running down hill. It was all too apparent how much was riding on his performance when he stole the show on stage alone during a “conversation” with the in-laws. At this point in the play, the wedding preparations are in high gear; the ex-boyfriend has arrived and is hidden in the bathroom; and ‘ding dong’ the future in-laws are at the door. In a drunken frenzy (yes, the father of the bride – trying to keep everything under wraps – has had a few stiff ones already) Doc Coleman must turn the in-laws around and send them to a hotel. In this production, there are no actors playing the in-laws. So the audience sees only Doc juggling lies, polite courtesies and suitcases into an open doorway. The scene lasted a glorious 10 minutes and stole the show.

The path of the show was interesting to me, and probably thought to be interesting to many since it was the main press release nugget written about in all the reviews. To have a show written 30 years a go, workshopped for almost 10 and now to be produced with the original three musketeers was sweet. I was trying to think of another way to say it but in the 80’s pastel vein of the show, sweet seemed the most appropriate. It reminded me how important education and finding your peers can be, how long lasting these bonds are when forged during a period of such growth and self-discovery. There are many companies and partnerships that have been developed this way, too many to even chip at. The one thing that it underlines in my mind is that education and community is vitally important. Through these new unions, greater work evolves and maybe not immediately but when the time is right.

So, on the path of education, I signed up for a Master Class at Jacob’s Pillow taught by this year’s Jacob Pillow Dance Award recipient, Crystal Pite. In America, she is still under the radar, but after what I experienced at Jacob’s Pillow both in the studio and in the audience, I don’t think she’ll be low flying for long. In 1990, her choreography debuted at Ballet British Columbia, going on to create works for companies such as Nederlands Dans Theatre (where she is currently Associate Choreographer), The National Ballet of Canada, Les Ballets Jazz de Montréal (Resident Choreographer, 2001-2004), Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet and independent artists, most recently Louise Lecavalier. Branching out to explore her distinctive dance theatre style, Pite formed Kidd Pivot in 2001creating Uncollected Work, Double Story, Lost Action, Dark Matters and The You Show.

Knowing all this and watching as many YouTube videos as I could find of her work, I was thrilled to get back in the studio to take her Master Class in Improvisation. Luckily, I was able to physically experience her work before being blown away by her company’s performance of Dark Matters. I don’t think I would have been able to tackle a class after the show because my brain was spinning. It took me a 45 minute car ride home and a few more hours telling other about the show and my experience to settle down a bit.

The master class focused on individual improvisation, exploring how the body moves by articulating different body parts. For example, leading with the left ear, then the right knee, etc. This is not new to me, I do this often in my work but how Pite’s explored these levels was the key I needed to advance myself in this work.

She started first with exploring the pelvis as the main movement source, then the chest and then the head. Each main body part was the leader of the body changing where it wanted to go and what it was focused upon. She spoke of ripples or echoes in the body. That when, for example, the right hip is leading, the rest of the body doesn’t know where it’s going – not in a victim or forceful way – but in a naïve way, chain reaction manner. This made me play with balance, speed and especially energy/impulse. Without a strong impulse, the ripples would not extend very far into and out of the body. It forced me to commit to the movement not knowing what the outcome might be. It was thrilling, scary and liberating.

Pite led the class to then focus on their feet and how the feet address the ground, including the sides and tops of the feet. As the feet lead, she guided us to explore not only the ground but the air and our legs with our feet, bringing the improvisation back to the source of the body, not only outward. All the while we were encouraged to move through the space aware of others around us, being inspired by their movements, incorporating or countering them. Finally, she had us explore our fingers and hands in symmetrical and then asymmetrical movements. She wanted us to go to the hands last because they the most common body part used for communication and as artists it is easy to take them for granted and stop exploring their potential.

Next, we went across the floor in pairs, alternating leading body parts (feet or head) with our partner. This was negotiated without talking, keeping a tight focus, in and out of each other’s negative space. It was interesting how some dancers were comfortable seeing their partner and others were solely focused on their own work. She would coach us to connect, look at each other, but this to me seems to be the unspoken bridge between theatre and dance – emotional relationship, which is what looking at each other develops. It was wonderful to observe her and her company members, who joined us in the master class, subtly raising the bar in the room. The care they took with their partner’s ideas/impulses and the commitment to the exploration was inspiring.

Another partner exercise had one dancer call out different body parts for the other to lead with, switching as fast or slow as necessary to extend the exploration. After switching leads, we then danced at the same time calling out body parts for the other dancer. The push and pull between thought and action was so interesting and frustrating all at the same time. We talked of the challenge of being aware during an improvisation enough to react to others and potentially recreate, but that this goes again the need to be open to any impulse, aka not planning or thinking while doing the improvising.

We ended with a group improvisation about space, timing and, though Pite did not make this distinction, tapping into the group consciousness. The exercise was merely this: everyone took a place against the three walls of the room (the fourth wall was taken by audience members since this was an open master class). Either you are off stage, the wall, or on stage. Each dancer walks on stage, stands and then walks off stage. You can do this wherever you like and for as long as you like. She was going to play a piece of music roughly seven minutes long to contain it. She said the hope is that at some moment everyone will be on stage and at another, final moment everyone will be off stage – without planning or speaking about it. I ate this up. This exercise fits right in with my work studying the collective consciousness and how it can help strengthen an artistic ensemble. It worked beautifully and it showed right away those who were aware of their surroundings and comfortable in their skin. Those that were trying to prove something or extremely nervous, second guessing themselves or pushed the moment beyond what it naturally wanted to do.

All in all, it was a wonderful experience as a teacher, choreographer and dancer. Her flow in class and light-hearted nature felt very much like how I try and orchestrate a workshop. It was helpful to feel it from the student’s perspective. It was also great to have her company members in the class. This says a lot to me about how she runs her company, understanding that class is essential as well as the community building involved in not only seeing the dancers on stage. And on top of all this, Pite was a new mom with a six-month old son waiting for her after the workshop. All things I needed to experience to keep me moving forward on my path… leading to experiencing her stunning production, Dark Matters.

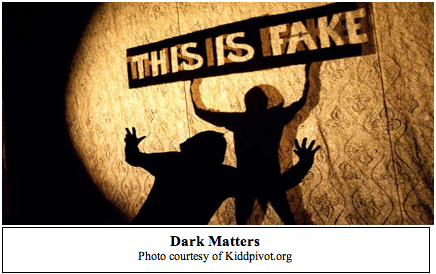

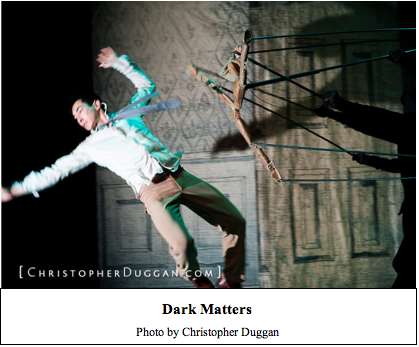

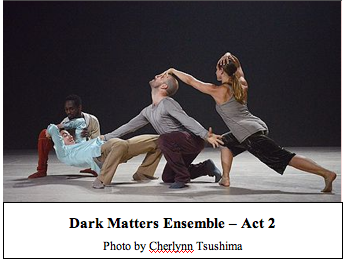

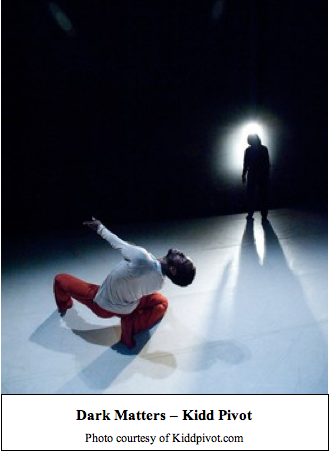

Dark Matters is a dance theatre piece in two acts focusing on the manipulative nature of relationships and that which we can not see that influences our life, the dark matter. As said in the program notes, “Comprising roughly 96 percent of the observable universe, dark matter affects the speed, structure and evolution of galaxies, yet its nature remains a mystery.” 5

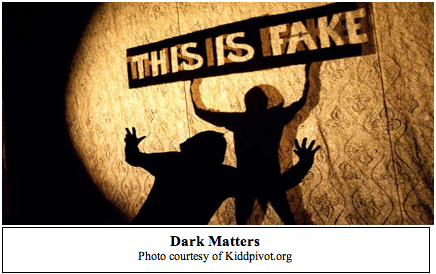

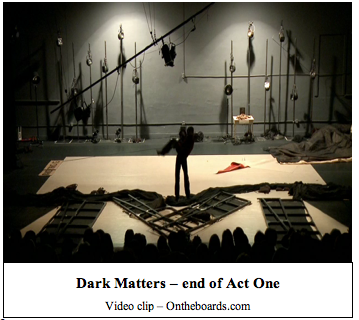

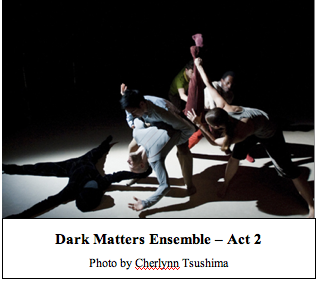

The show starts off with a roaming spotlight that only allows us to see snippets of a man’s workshop table. A voice over of a man speaking Voltaire’s “Poem on the Lisbon Disaster” is heard. This text is then chopped up and heard through out the performance at different times. The first act is very theatrical, a mysterious horror tale of creator and his creature. A man creates life, a puppet animated by five ensemble members dress all in black, that he raises and then ignores. The puppet turns on its creator and kills him, only to die itself shortly thereafter. The puppeteers, or dark matter, then begin to clean up the mess left from the violent murder. But one comic character starts playing with its shadow on the wall, which evolves into a superhuman power used to combat the other dark matter beings in a larger than life karate section. Humorous and seemingly out of place, it all comes to a wonderful punchline with another dark matter being walks onstage with a broom, sees the “superhuman” figure, looks at the light that was casting the shadow and turns it off. Instantly we see that the creature had been daydreaming thus cutting the “dark” tone into a childlike one. We now had to see these creatures in a different light. One bumps into a flat and it starts to tear a bit. These intrigues others until the next thing we know the entire set is being ripped apart, not physically with their hands but with their intention.

The Marley floor is pulled up in sections, an entire row of lights hangs precariously over the stage, the flats crash to the ground. All the dark matter beings, save one are killed under the rubble. The surviving creature sees the body of the human creator under the Marley floor. Through a beautiful solo/duet, the creature animates the man, much like animating a puppet, and helps him exit the stage.

The Marley floor is pulled up in sections, an entire row of lights hangs precariously over the stage, the flats crash to the ground. All the dark matter beings, save one are killed under the rubble. The surviving creature sees the body of the human creator under the Marley floor. Through a beautiful solo/duet, the creature animates the man, much like animating a puppet, and helps him exit the stage.

Then, seeing another creature under a flat, the surviving dark matter creature uncovers them and cradles them in their arms, walks down stage center to face the audience and in one swift move chucks the body at a pile of wooden flats. The audience, myself included, gasp at the horror only to realize we had been fooled and this was a dummy. Blackout. We were asked to leave the theatre for intermission so the second act could be set up.

The second act was an extension of the theme but danced by the ensemble in street ware, except for the surviving dark matter creature from act one. Even the creator from act one was now part of the dance ensemble. The phrases were desperate and heartbreaking, with people grasping at each other like lifelines. One section had five dancers moving together in a relationship chain reaction. What was amazing was when this same section was repeated later in the piece and the dark matter creature was inside these relationships, almost causing them. So we got to see what we all see first, the outer effects of life, and then the behind the scenes suggestion that dark matter influences these decisions. The choreography never changed and yet the dark matter creature’s role was vital. It made me wonder how they did it without her the first time!

lifelines. One section had five dancers moving together in a relationship chain reaction. What was amazing was when this same section was repeated later in the piece and the dark matter creature was inside these relationships, almost causing them. So we got to see what we all see first, the outer effects of life, and then the behind the scenes suggestion that dark matter influences these decisions. The choreography never changed and yet the dark matter creature’s role was vital. It made me wonder how they did it without her the first time!

The roaming spotlight comes back in a different capacity in the second act. The dark matter creature moves a light on casters around the stage focusing tightly on some actions and exaggerating the shadows of another. It was subtle and a wonderful effect.

The piece ends with the surviving dark matter, left alone on stage, slowly stripping off her black costume revealing a woman in a nude bikini. She encounters the dancer who played the creator in Act One and they begin a duet that explores vulnerability and innocence. The stage is black with tiny lights in the foreground evoking the image of stars in the heavens. The two dancers exchange lead roles and vulnerable moments all leading up to a surprise kiss and the development of love. But in the heighten emotions, the dark matter woman reaches for the man as he runs to her and her arm stabs through him – a clear parallel to the puppet creature stabbing his creator in Act One. Beside herself, she drops to her knees cradling the dying man and slowly she starts to stitch up his heart… and the cycle of love and destruction continues. Blackout.

The piece ends with the surviving dark matter, left alone on stage, slowly stripping off her black costume revealing a woman in a nude bikini. She encounters the dancer who played the creator in Act One and they begin a duet that explores vulnerability and innocence. The stage is black with tiny lights in the foreground evoking the image of stars in the heavens. The two dancers exchange lead roles and vulnerable moments all leading up to a surprise kiss and the development of love. But in the heighten emotions, the dark matter woman reaches for the man as he runs to her and her arm stabs through him – a clear parallel to the puppet creature stabbing his creator in Act One. Beside herself, she drops to her knees cradling the dying man and slowly she starts to stitch up his heart… and the cycle of love and destruction continues. Blackout.

The ensemble was spectacular on many levels. The puppeteering, which was done by the dancers, was highly effective. At times it felt like watching a child as the puppet demanded attention and was hurt when shoved away. I found myself pitying the poor creature and it was an assemblage of wooden shapes manipulated by 5 long sticks. Amazing. The dancing was as if they themselves were puppets, such sharp movement that seemed to move them not the other way around. When I first watched the trailer for this piece, I had to stop and rewind, thinking that some of the choreography was done with film editing and manipulation of tape speed. Seeing it live, it was still hard to believe. The ripples, the control, the dexterity it was inspiring. The fluidity was also stunning in the sense that it looked so organic that it was hard to see how one could choreography it, and yet it was, obviously when phrases where repeated move for move. There is also a large chunk of ensemble improvisation that is seamless within the piece. I would have only known about it because of the discussion about it in the previous master class. The transitions were flawless and the improvisations were of such a level that they fit directly into the choreography and intention of the piece, never watering down the action or momentum. True ensemble work in action and true directorial work to know when to step out of it and let the ensemble do that which one person would not be capable of.

The theatricality of the piece was wonderful and I think a great blend or hybrid for dance audiences. The first act set the tone for narrative with both the linear snapshot moments of the creator making his creature, to the lines of text and original score by Owen Belton that was both melodramatic and spacious. The constant twists and turns that Pite directed into the piece helped to keep the audience off balance, keeping us thinking and feeling at the same time. How very Brechtian of her to utilize this alienating effect! And to top it off, her choreography is this balance too of thinking and feeling. The dancers became puppet like manipulating other through touch impulses to different joints as well as manipulating themselves.

The theatricality of the piece was wonderful and I think a great blend or hybrid for dance audiences. The first act set the tone for narrative with both the linear snapshot moments of the creator making his creature, to the lines of text and original score by Owen Belton that was both melodramatic and spacious. The constant twists and turns that Pite directed into the piece helped to keep the audience off balance, keeping us thinking and feeling at the same time. How very Brechtian of her to utilize this alienating effect! And to top it off, her choreography is this balance too of thinking and feeling. The dancers became puppet like manipulating other through touch impulses to different joints as well as manipulating themselves.

This piece was a long time in the making. Having seen her previous work, there are apparent threads: the idea of dark matter, puppets and improvisation inside set choreography. I was enjoyable seeing, after the fact, how these little pieces were sewn together to create such a production. It felt like she was tackling a larger than life theme in bite-sized pieces over the years. What a smart way of exploring without the heaviness of trying to put it all in one piece right from the beginning.

I noticed that everything I saw this summer was based in ensemble work. With this semester focusing on Sole Ownership, I must say this: even though I was captivated by the overall art of the ensemble, it was the individuals that pulled me in – the directors, the writers, the performers on their own. I was drawn to the heightened level commitment and the risks taken by the individual that was ultimately supported and elevated by the group. Even more inspiration came after the experience in the audience seat, while I was researching the creators: their past, their goals, their future. The fact that these individuals chose to do ensemble work is part of what makes them who they are. Not everyone is drawn to collaborations of this nature. And to see how the directors and choreographers still had the final voice while developing a tight knit ensemble is very intriguing to me.

This paper allowed me to analyze not only my immediate reactions to the shows or class, but also to look at the common themes that draw me to these pieces. My hope is that this type of critical analyze will help me hone in on the type of teacher and artist I am reflected by the type of student and audience member I am.